Yarn Weights and Rigid Heddle Dent Sizes: What the Numbers Mean

Every rigid heddle loom in America is measured in teeth. Literal teeth. Per inch.

Someone, somewhere, looked at those evenly-spaced slots in a loom reed and thought that looks like a comb and now here we are, two centuries later, counting dental arrangements to make fabric. An 8-dent reed? Eight teeth per inch. A 12-dent? Twelve. It's beautifully literal in a world that rarely is.

Meanwhile, yarn exists in its own universe of poetry. Fingering weight. Lace weight. Something called "sport" that has nothing to do with athletics. DK means "double knitting" – a term from when British grandmothers ruled the yarn world and everyone knew exactly what that meant. Worsted? Named after Worstead, England, where they spun yarn so consistently in the 12th century that eight hundred years later, we're still using their village name to describe medium-weight acrylic from China.

The beautiful chaos is that these two systems – teeth-counting and medieval yarn poetry – have to work together. Like a NASA engineer trying to dance with a Renaissance poet. They don't speak the same language. They don't use the same math. One's metric, one's imperial, and some companies just make up their own numbers because why not?

But watch what happens when weavers get hold of this chaos. They turn it into cloth. Consistently. Predictably. They've built conversion charts that would make mathematicians weep – wraps per inch, sett calculations, something called the Ashenhurst formula that sounds like alchemy but actually works. They've mapped every possible yarn weight to every possible reed size through pure determination and probably thousands of failed dishcloths.

The numbers aren't just measurements. They're a kind of textile DNA, encoding centuries of knowledge about how threads behave when you force them to live next to each other.

The Yarn Weight System: A Beautiful Mess

The Craft Yarn Council – yes, that's a real organization – maintains something called the Standard Yarn Weight System. They've assigned numbers 0 through 7 to yarn weights, presumably because someone finally got tired of explaining what "fingering" meant to confused beginners.

Here's their system: Lace weight gets a 0. Fingering gets a 1. Sport is 2. DK is 3. Worsted is 4. Chunky is 5. Bulky is 6. Jumbo is 7. Clean, logical, sequential. Except nobody uses these numbers. Walk into any yarn shop and ask for "category 4 yarn" and watch the sales assistant's face. You'll get worsted weight yarn eventually, but only after they figure out you're speaking Council.

The traditional names stick around because they carry information the numbers don't. "Worsted" tells you something about how tightly spun the yarn is, not just its thickness. "Fingering" weight got its name from being fine enough for the fingers of gloves – that's actually useful context. "Sport" weight was originally used for sporty garments that needed to be lighter than regular knitting. These aren't random names; they're compressed history lessons.

But here's where it gets genuinely interesting: yarn weight isn't actually about weight at all. It's about thickness. A pound of lace weight yarn and a pound of bulky yarn weigh the same – obviously – but one will give you enough thread to wrap around the earth and the other will make maybe three hats. The "weight" classification describes how much space the yarn takes up, not what it tips the scales at.

Manufacturers measure this thickness in wraps per inch (WPI). They literally wrap yarn around a ruler and count how many times it fits in an inch. Lace weight? 35+ wraps. Fingering? 14-16. Worsted? 9-10. Bulky? 5-7. It's analog measurement in a digital world, and somehow it's still the most reliable system we have.

Dent Sizes: Counting Teeth Since Forever

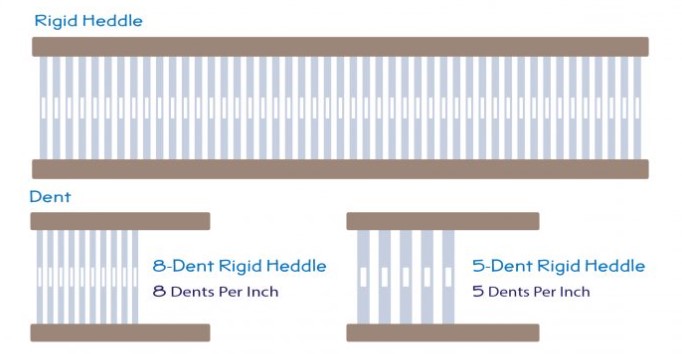

Now for the loom side of this equation. "Dent" comes from the French word for tooth, because early reed makers apparently looked at their creation and saw a very wide smile. Each dent is actually a gap – the space between the rigid heddle's teeth where the yarn passes through. When someone says "8-dent reed," they mean eight gaps per inch. Not eight teeth. Eight spaces between teeth. It's the negative space that counts.

The physical reality of these reeds is surprisingly precise engineering. Those teeth? They're typically made from either strong plastic (in modern looms) or steel (in older or high-end versions). They have to be exactly equidistant. A variation of even 1/32 of an inch throws off the entire fabric structure. Manufacturers use injection molding or precision cutting to maintain tolerances that would impress a watchmaker. Working with these tiny measurements means good lighting is essential – squinting at heddle slots in poor light is a recipe for frustration. Many weavers swear by dedicated craft lighting to actually see what they're doing when threading these precise spaces. The wooden components of quality looms often receive protective finishes like Danish oil to maintain dimensional stability in these tight tolerances.

Schacht, the Colorado-based company, makes reeds in 5, 8, 10, 12, and 15 dents per inch. They stick to imperial measurements because they're American and that's what American weavers expect. Ashford, from New Zealand, offers 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10, 12.5, and 15. They're metric, but they convert to imperial for the US market, which is why you get that slightly insane 7.5 dent option. It's actually 3 dents per centimeter. The math checks out, even if your brain doesn't want it to.

The range tells you something about market demand. Nobody makes a 20-dent rigid heddle because at that point, the yarn would be so fine you'd need a magnifying glass to see it. Nobody makes a 1-dent because you'd be weaving with rope. The sweet spot – where most weaving happens – is between 7.5 and 10 dent. That's the workhorse range. The bread and butter. The zone where dishcloths are born.

The Translation Table Nobody Explains

Here's what actually happens when yarn meets reed. The relationship between yarn weight and dent size determines something called "sett" – how many threads per inch you pack into your fabric. Pack them too tight, and you get cardboard. Too loose, and you get fishnet. The sweet spot creates what weavers call "balanced" fabric, where the threads have just enough room to bloom but not enough to migrate.

| Yarn Weight | Yards per Pound | Wraps per Inch | Compatible Dent Sizes | Craft Yarn Council Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lace | 5,000+ | 35+ | 12-15 dent | 0 |

| Fingering | 1,900-2,400 | 14-16 | 10-12 dent | 1 |

| Sport | 1,200-1,800 | 12-14 | 8-10 dent | 2 |

| DK (Double Knitting) | 1,000-1,200 | 11-12 | 8 dent | 3 |

| Worsted | 900-1,000 | 9-10 | 7.5-8 dent | 4 |

| Aran/Heavy Worsted | 700-900 | 8-9 | 5-7.5 dent | 4 |

| Bulky | 400-600 | 5-7 | 5 dent | 5 |

| Super Bulky | 200-400 | 4-5 | 2.5-5 dent | 6 |

Notice those overlaps? That's where the magic happens. A sport weight yarn in an 8-dent reed gives you one fabric. The same yarn in a 10-dent reed gives you something completely different – lacier, drapier, more open. The numbers are starting points, not destinations.

The yards-per-pound measurement is the secret decoder ring of the yarn world. It's the only objective measurement that actually tells you something useful. Manufacturers weigh out a pound of yarn and measure how many yards they get. More yards equals thinner yarn. It's brutally simple and completely reliable. A yarn labeled "worsted" by one company and "aran" by another might both measure 950 yards per pound. That number doesn't lie, even when marketing does.

What Manufacturers Actually Do

Yarn companies don't actually test their products in every possible reed size. They test in maybe two or three standard configurations and extrapolate from there. Lion Brand might run their Wool-Ease through an 8-dent reed, confirm it works, and call it good. They're not checking 7.5, 10, and 12 dent options. That's on you.

What they do provide – sometimes – is something called "gauge." That's knitting terminology that leaked into weaving. It tells you how many stitches per inch you'd get if you were knitting with their yarn on a specific needle size. Weavers have learned to translate this: if a yarn knits at 4 stitches per inch, it'll probably work in an 8-dent reed. It's not science. It's barely even math. But it works often enough that people keep doing it.

The reed manufacturers have their own approach. Schacht includes a project guide with their looms suggesting yarn weights for each reed size they sell. Ashford does the same. These aren't based on extensive laboratory testing. They're based on decades of customer feedback, returned products, and workshop observations. When Ashford says their 7.5 dent reed works with DK weight yarn, they mean thousands of weavers have done it successfully enough that the company feels safe printing it in a manual.

The truth is that most rigid heddle loom manufacturers buy their reeds from the same handful of suppliers. There's a factory in Taiwan that makes reeds for at least three major brands. They're all using the same injection molds, the same plastic formula, the same spacing. The only difference is whose logo gets stamped on top.

When Systems Collide

The real complexity appears when you start mixing yarns. Say you want to use a fingering weight cotton for warp and a sport weight wool for weft. The cotton measures 2,000 yards per pound. The wool measures 1,400. Your 10-dent reed doesn't care about this philosophical crisis you're creating. It just holds threads at specific intervals.

What happens in practice is that weavers develop intuition about thread behavior that transcends the numbers. They learn that cotton doesn't compress like wool, that silk slides differently than alpaca, that handspun yarn laughs at all attempts to categorize it. A handspun "worsted" might vary from fingering to bulky within the same skein, and somehow, rigid heddle weavers make it work.

The Ashenhurst formula – developed in the early 1900s for industrial looms – tried to mathematize all this. It uses yarn count, weave structure, and desired fabric characteristics to calculate optimal thread spacing. The formula looks like this: Threads per inch = √(Yarn count × Fabric firmness factor). Rigid heddle weavers ignore it completely. They use something called the "wrap test" instead: wrap yarn around a ruler, count wraps in an inch, divide by two. That's your sett. It's wrong, technically, but it's wrong in a way that usually works.

The Metric-Imperial Dance

The measurement chaos deepens when you realize half the weaving world uses metric and half uses imperial. A New Zealand pattern calling for 8 wraps per centimeter means... what exactly? That's roughly 20 wraps per inch, which would typically need a 10-dent reed, except the pattern was written for a 4-dents-per-centimeter reed, which is actually a 10-dent reed, so it works out, but only if you squint.

European weavers count threads per centimeter. Americans count per inch. Australians do whatever they feel like. Japanese weavers use a completely different system based on traditional measurements that predate standardization. Everyone publishes patterns assuming their system is universal. The internet brings all these patterns together in one glorious babel of incompatible measurements.

Reed manufacturers have mostly given up. Glimakra, the Swedish company, publishes specifications in both systems and lets weavers figure it out. Some companies have started using both measurements on the same reed – "10 dpi / 4 dpcm" – which looks like a math equation but at least eliminates confusion.

The Reality of Modern Manufacturing

Here's something the traditional measurements don't account for: modern yarn isn't made like historical yarn. That "worsted weight" acrylic from Red Heart has never been near a sheep. It's extruded from petroleum products through spinnerets at exactly 1.2 millimeters diameter. The thickness is controlled by computers, not spinning wheels. It's more consistent than any hand-spinner could achieve, but it also behaves nothing like actual worsted-spun wool.

Bamboo yarn – which is really rayon made from bamboo pulp dissolved in caustic soda – gets labeled with traditional weight categories despite having completely different properties. It's denser than wool, shinier than cotton, and drapes like silk. Calling it "DK weight" tells you almost nothing about how it'll behave in a rigid heddle loom.

Yarn companies keep using the traditional terminology because that's what consumers understand. Nobody wants to learn a new system. The knitters and crocheters vastly outnumber the weavers, and they're perfectly happy with their fingering-sport-DK-worsted progression. Rigid heddle weavers just have to adapt.

Some companies have started adding actual measurements to their labels. Cascade Yarns prints the wraps per inch right on their bands. WeCrochet includes meters per gram. These numbers mean something. They're measurable, verifiable, reproducible. But most weavers still reach for the yarn that "feels right" and figure out the math later.

The Bottom Line in 2025

The collision between yarn weights and dent sizes produces functional fabric through what can only be described as collective faith. Thousands of weavers worldwide are using mismatched measurement systems, improvised conversion charts, and instinct developed through repetition. They're making beautiful things.

The numbers – those teeth per inch and yards per pound – are just the opening vocabulary of a much larger conversation between thread and loom. They're useful the way training wheels are useful. Eventually, weavers develop what they call "hand" – the ability to feel whether a yarn will work in a particular reed just by squishing it. No math required.

The manufacturers know this. That's why Schacht still ships their Cricket looms with 8-dent reeds even though 10-dent would be more versatile. They know beginners need a starting point that works with grocery store yarn. That's why Ashford offers 2.5 dent reeds even though hardly anyone uses them. Someone, somewhere, is weaving rag rugs and needs those wide gaps.

The system works because it's flexible enough to accommodate both precision and improvisation. You can follow the charts exactly and get predictable results. Or you can grab whatever yarn appeals to you, pick a reed that seems reasonable, and see what happens. Both approaches produce cloth. Neither is wrong.

What the numbers really mean, in the end, is that humans have been trying to organize thread for so long that we've developed multiple, incompatible systems for describing the same thing. And instead of picking one, we just... use them all. Simultaneously. With conversion charts that everyone pretends are more scientific than they actually are.

That's weaving. That's craft. That's the beautiful, functional chaos of making things with your hands in 2025.