Isamu Noguchi: When Sculpture Became Furniture You Could Actually Touch

Isamu Noguchi made a coffee table as an act of revenge. A furniture designer named Robsjohn-Gibbings asked him to design something in 1939, so Noguchi created a small plastic model and left it for review. Then nothing. Radio silence. He headed west to work on other projects, figured the commission fell through.

When he came back, Robsjohn-Gibbings had taken Noguchi's design and was using it as his own. Worse - George Nelson, Herman Miller's design director, had seen it and wanted to feature it in an article called "How to Make a Table." Noguchi confronted Robsjohn-Gibbings. The response? "Anybody could make a three-legged table."

So Noguchi made his own variant of his own table. Named it after himself. Made sure nobody could ever forget who designed it. That table - with its two interlocking pieces of wood supporting a heavy glass top - now costs $2,695 from Herman Miller and sits in the Museum of Modern Art's permanent collection.

The revenge worked spectacularly.

What $2,695 Actually Buys You

Herman Miller charges $2,695 for an authentic Noguchi table in 2026. The signature gets etched into two places - the glass edge and a medallion underneath the base. You're buying authentication as much as furniture.

Here's what makes the original different: 3/4-inch thick tempered glass that weighs enough to need two people to move it. Solid hardwood base pieces that interlock at a single pivot point to create a self-stabilizing tripod. Hand-finished wood in walnut, white ash, natural cherry, or black. The kind of finish that doesn't look shiny - it looks like the wood grain has opinions about light.

Replicas run $400-1,200 depending on how much the manufacturer cares about getting the details right. The cheap versions use thinner glass and hollow wood. Mid-tier reproductions match the dimensions and use solid wood, but the finish looks too glossy. The wood treatment makes the difference - Herman Miller's version has this matte quality that makes the grain visible without being shiny about it.

The design itself can't be patented anymore. It's been 75+ years. What Herman Miller owns is the trademark on the specific configuration and the right to stamp Noguchi's signature on it. Every other manufacturer makes "triangle coffee tables" or "sculptural glass tables" - anything to avoid saying "Noguchi" without permission.

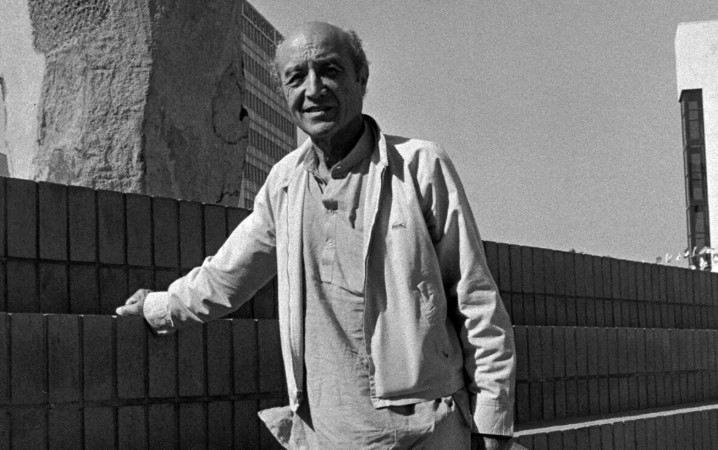

The Man Who Belonged Nowhere

Los Angeles, 1904. Isamu Noguchi got born into a situation with no good answers. Japanese father who was a famous poet. Irish-American mother who was a writer. His father refused to marry his mother or acknowledge Isamu legally. So his mother took him to Japan when he was two, thinking the boy needed to know his Japanese heritage.

Japan didn't want him either. Mixed-race kid in 1900s Japan? He was gaijin - outsider - no matter what his last name said. His mother sent him back to Indiana at thirteen. Indiana didn't particularly want him either, but at least they let him attend school.

That belonging-nowhere thing? It shaped everything he made. Noguchi spent his life translating between cultures that both claimed him and rejected him. Japanese aesthetics filtered through American manufacturing. Western sculpture techniques applied to Eastern materials. He worked in stone, metal, wood, clay, bone, paper - whatever let him say what he needed to say.

"Everything is sculpture," he said. Not as a metaphor. He meant it literally. A coffee table could be sculpture. A paper lantern could be sculpture. A playground could be sculpture. Even light itself - immaterial and weightless - could carry sculptural presence.

The Internment Nobody Required

February 1942. Executive Order 9066 forced Japanese Americans on the West Coast into internment camps. Noguchi lived in New York. The order didn't apply to him. He was exempt. Safe.

He voluntarily entered the Poston War Relocation Center in Arizona anyway.

His reasoning made a certain idealistic sense at the time. He'd formed the Nisei Writers and Artists Mobilization for Democracy, trying to prevent the internment from happening. That failed. So he thought maybe he could make the camps more humane from inside. He'd talked with John Collier, the Commissioner for Indian Affairs, about creating craft guilds and recreational spaces. Beautify the camps. Give people dignity while imprisoned.

He designed blueprints for Poston that included a botanical garden, a zoo, a miniature golf course, a cemetery with proper landscaping. He specified which flowering plants would look best in different seasons. He wanted to organize lectures on Japanese art and offer vocational training in ceramics and woodworking.

None of it happened.

The government never sent the materials. The other internees didn't trust him - they saw a famous Manhattan sculptor who could somehow still purchase art supplies and work on commissions while they couldn't leave the barbed wire. Camp administrators treated him with suspicion. After two months, Noguchi realized nothing would change. He applied to leave.

They denied his request. Suspicious activities, they said. It took seven more months before they let him go. Seven months of understanding exactly how thoroughly his idealism had failed, how much his dual heritage marked him as perpetually suspect.

He walked out in November 1942 with a piece of carved driftwood the size of a palm, shaped like a teardrop. And rage. Lots of rage.

What Anger Produces

Back in his New York studio, Noguchi made sculptures that weren't subtle about what they meant. "This Tortured Earth" (1942-43) showed a landscape scarred with gashes and pits - a proposal for a war memorial that depicted earth as wounded flesh. No soldiers. No heroes. Just the land itself, clawed to pieces.

"Yellow Landscape" (1943) - and yeah, that title is exactly the racial slur you think it is - featured three different weights delicately strung together, hanging over barren ground. Precarious balance. The threat of collapse. Everything suspended by threads that might break.

For four years after Poston, his work stayed explicitly political. Then gradually the direct references faded. But the desert never left his sculptures. Twenty-five years later he made "Double Red Mountain" (1969) - two mountain forms rising from Persian travertine that captured the austere vastness of Arizona's landscape. The experience burrowed deep. It stayed there.

"I was finally free," he said after leaving Poston. "I resolved henceforth to be an artist only." As if he could separate art from politics. As if the experience hadn't fundamentally shaped everything he'd make afterward.

The Table That Became an Icon

The coffee table story starts in 1939 with that original commission from Robsjohn-Gibbings. But the actual production story starts in 1947, after the war, after Poston, after Noguchi had spent years proving he was just a sculptor, not a threat.

George Nelson at Herman Miller recognized the design's potential - whether he knew about the Robsjohn-Gibbings theft or not. Noguchi's original table (the one he'd made for A. Conger Goodyear, president of the Museum of Modern Art, in 1939) had sold at auction in 2014 for $4.45 million. The design worked. The question was whether mass production could maintain what made it work.

Herman Miller introduced the Noguchi table in 1947. Two identical curved wood pieces that interlock at a single point. Heavy plate glass top - originally 7/8-inch thick, later reduced to 3/4-inch in 1965. The base was offered in birch, walnut, and cherry initially. Cherry bases only lasted one year of production. Too expensive. Birch got discontinued by 1954. Walnut became the standard.

Production got pulled in 1973. The table became collectible immediately - one of those things that's more valuable when you can't buy it new. Herman Miller did a limited edition in 1980, testing interest. Strong enough that they reissued it permanently in 1984. It's been in continuous production since.

The design works because it's genuinely sculptural while remaining functional. That heavy glass top isn't decoration - it's structural counterweight. The curved wood pieces look delicate but form a tripod that's self-stabilizing. Move the table and it stays balanced. The design reveals its logic while hiding its complexity.

Noguchi called it his one true success. Not the gardens he designed for UNESCO. Not the fountains at Tokyo's Supreme Court Building. Not the massive public sculptures. The coffee table. The thing people actually lived with. "Everything is sculpture" meant sculpture should exist in everyday life, not just museums.

Paper Moons That Changed an Industry

Gifu, Japan, 1951. Noguchi visited a town known for making paper lanterns from mulberry bark and bamboo. The industry was dying. World War II had wrecked Japan's economy. The lanterns that remained were cheap advertising decorations - the kind of thing nobody wanted and everybody ignored.

The mayor of Gifu asked Noguchi if he could help. Revitalize the lantern industry. Create something modern for export. Make paper lanterns matter again.

Noguchi came up with two prototypes the next day. A local newspaper described them as "deformed." He'd taken traditional chochin lanterns - the kind used by cormorant fishermen to light their boats at night - and replaced the candle with an electric lightbulb. Instant modernity. He called them Akari, Japanese for "light" with associations to both illumination and weightlessness.

He partnered with Ozeki & Co., a company founded in 1891 that had survived the industry collapse. They'd make wooden molds. Stretch bamboo ribbing across the forms. Glue strips of handmade washi paper (from mulberry bark inner fibers) onto both sides of the framework. Once dry, collapse and remove the internal wooden mold. What remained was a collapsible paper lantern that could ship flat worldwide.

Noguchi designed over 200 models of Akari between 1951 and his death in 1988. Hanging versions. Standing versions with metal stems. Columnar shades. Spheres. Cylinders. Abstract shapes that looked organic without copying nature directly. Each one handmade in Gifu using the same traditional process, just applied to contemporary forms.

The lamps became ubiquitous. You've seen them even if you don't know the name - those glowing paper spheres in modern living rooms, restaurants, design shops. IKEA makes knockoffs. Everyone makes knockoffs. The paper lantern form itself couldn't be patented - it predated Noguchi by centuries. What he could patent were the metal armatures, the stands, the hardware. Which he did. Five American patents, thirty-one Japanese patents. Protecting what could be protected while accepting that imitation was inevitable.

Some art world people questioned whether Akari were "art" or "design" - as if the distinction mattered to anyone except critics. Noguchi just kept making more models. The lamps brought "sculpture into more direct involvement with the common experience of living." That was the point. Not museum walls. Living rooms. Bedrooms. Anywhere light was needed.

"All that you require to start a home," Noguchi wrote, "are a room, a tatami, and Akari."

What Mass Production Means for Sculpture

The Akari lights still get made in Gifu by Ozeki & Co., using the same handcraft methods. Each lantern takes hours to produce. Bamboo doesn't bend uniformly. Washi paper varies. Human hands create slight variations in every piece. That craft process limits production volume but maintains quality.

The Noguchi table gets manufactured to tighter tolerances. Herman Miller uses CNC machining for the wood base pieces, then hand-finishes them. The glass gets precision-cut and polished. Quality control catches variations that would pass in handcraft. The table that reaches your home is effectively identical to every other authentic table - which is both the point and a compromise with Noguchi's "everything is sculpture" philosophy.

Noguchi accepted that compromise. He wanted his designs accessible. Museums collect his large stone sculptures. Regular people buy his tables and lamps. Both matter. The museum pieces prove his artistic credibility. The mass-produced designs prove sculpture can exist in everyday life.

The replica market for the table is massive. You can find "triangle coffee tables" at every price point from $400 to $1,800. Most look approximately right until you compare them directly to an original. The proportions are slightly off. The wood curve isn't quite correct. The glass is thinner. Small differences that add up to feeling wrong.

The best replicas - the $1,200-1,500 tier - get close enough that only people who know the original well can spot the difference. Solid wood. Proper dimensions. Decent finish. They lack the Herman Miller signature, but they function identically. Whether that matters depends on how much you care about authentication versus having the design in your space.

The Museum That Became a Home

Queens, New York, 1985. Noguchi opened his museum in a converted factory building. Not a traditional museum - more like his working space made accessible. Sculptures inside and outside. A garden where stone pieces interact with plants and water. Spaces designed to show how sculpture relates to environment.

The museum building itself is sculpture. Noguchi designed it to display his work the way he envisioned it being experienced - not as objects on pedestals but as spatial presences. You walk through the galleries and the outdoor garden understanding how he thought about negative space, about weight and lightness, about materials having inherent properties that sculpture should reveal rather than disguise.

His career spanned six decades and basically every material humans work with. Stone sculptures that weigh tons. Paper lanterns that collapse flat. Bronze castings. Marble carvings. Wood constructions. Clay works. Furniture. Playgrounds. Gardens. Stage sets for Martha Graham's modern dance productions - he was the only designer Graham would work with for forty years.

The common thread was that belonging-nowhere thing made physical. East and West. Art and design. Public and private. Traditional and modern. Noguchi worked in the spaces between categories that other people insisted were separate.

What Actually Endures

Noguchi died in 1988, aged 84. The coffee table he designed out of revenge kept selling. The paper lanterns he created to save a dying industry kept glowing in homes worldwide. The sculptures he made about being neither Japanese enough nor American enough kept standing in museums and public spaces.

His Akari lights became so common that most people buying them have no idea they're getting functional sculpture. They see a paper lantern that looks cool and costs less than a designer lamp. The Herman Miller table sits in living rooms where people don't know Noguchi's name but recognize the design from somewhere.

That diffusion into everyday life - that forgetting of origin while keeping the form - is exactly what Noguchi wanted. "Everything is sculpture" means sculpture doesn't need to announce itself. It can be the light you read by. The table your coffee sits on. The playground equipment kids climb. The garden you walk through without thinking about whether it counts as art.

The internment camp experience gave him "Yellow Landscape" and "This Tortured Earth" - explicitly political works he made while the rage was fresh. But it also gave him the understanding that sculpture could exist outside gallery walls, that design could carry sculptural meaning, that the boundary between art and everyday objects was artificial.

The coffee table works because it's genuinely sculptural - the interlocking base, the heavy glass counterweight, the way it looks different from every angle. But it also works because it's just a coffee table. Holds your coffee. Supports your books. Functions normally while being extraordinary.

That's the trick Noguchi figured out. How to make sculpture people could actually touch, actually use, actually live with. How to bring form and function together without making either apologize for the other. How to be neither purely Japanese nor purely American while being entirely both.

The table costs $2,695 from Herman Miller or $600 from various replica manufacturers. The Akari lamps range from $200 for small versions to thousands for large sculptural pieces. The designs themselves - those specific forms that Noguchi invented as revenge, as industry revival, as spatial presence - are everywhere now.

Most people don't know his name. They just know the shapes work. That was always the point.