Eero Saarinen: The Architect Who Dissolved Furniture

Eero Saarinen hated looking under tables. "The undercarriage of chairs and tables in a typical room," he wrote in 1956, "creates an ugly, confusing, unrestful world." His solution sounds simple: eliminate the legs. The execution took five years, $70,000 in development costs (about $780,000 today), and produced a chair that appears to defy physics.

That chair – the Tulip – now sits in approximately 40% of luxury real estate staging photos, according to furniture rental companies. The Museum of Modern Art owns seven variations. Knock-off versions generate an estimated $50 million annually. The original from Knoll costs $2,692 for a single dining chair.

But here's what the design history books often miss: Saarinen considered the Tulip Chair a failure. He wanted the base and seat to be one continuous material, like a flower growing from the ground. Technology couldn't deliver. The fiberglass seat required an aluminum base, painted to match. He called it a "compromise" until his death in 1961.

The Finnish Connection Nobody Mentions

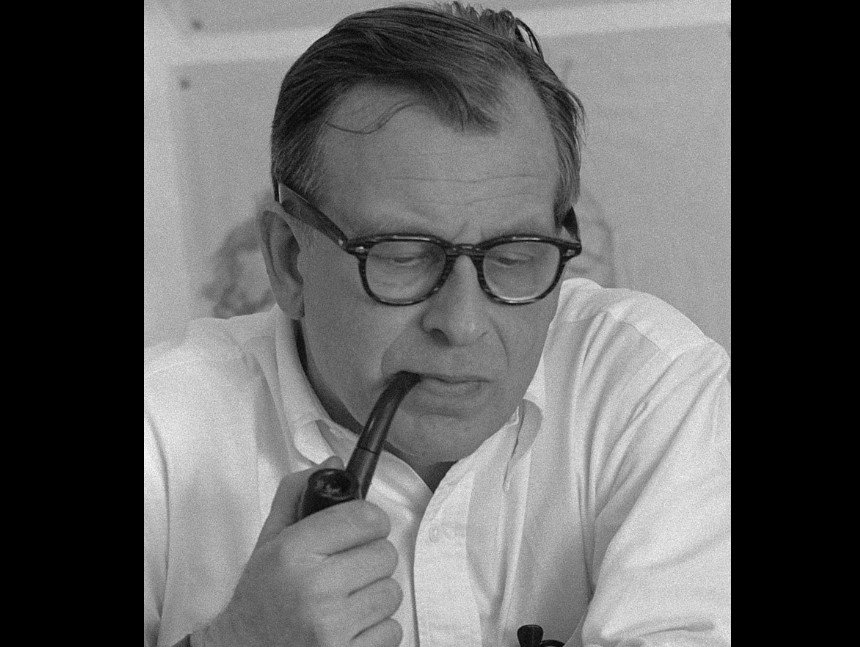

Eero Saarinen was born in Finland in 1910, but most biographies rush past this fact to get to his American career. The Finnish context matters. His father, Eliel Saarinen, was already Finland's most famous architect when Eero was born. Eliel designed the Helsinki Central Station – the building with the giant stone figures holding glowing orbs that every tourist photographs.

In 1923, Eliel came second in the Chicago Tribune Tower competition. The prize: $50,000. But here's the twist – his losing design influenced American architecture more than the winner. Louis Sullivan called it "the most beautiful building in the world." The family emigrated to America based on that loss.

They settled in Michigan, where Eliel designed the Cranbrook Academy of Art campus. Young Eero grew up on an active construction site that became America's most influential design school. His playground was a Modernist laboratory. Charles and Ray Eames met there. Florence Knoll studied there. Harry Bertoia taught there. George Nelson would later hire many Cranbrook alumni for his studio. The network that would dominate mid-century design formed in Eero's backyard.

The family operated as an informal firm. Eero's mother, Loja, was a textile designer and sculptor. His sister Pipsan became an interior designer. Dinner conversations were design critiques. When Eero was 12, his father had him redesign the furniture for his bedroom. The boy spent three months on the project.

The Womb Chair Economics

In 1946, Florence Knoll approached Saarinen with a specific request: "I want a chair I can curl up in." She was pregnant at the time. The brief was personal, but the market opportunity was massive. Post-war Americans were building suburban homes with larger living rooms. They needed furniture that worked for both formal entertaining and casual television watching.

Saarinen's response took two years to develop. The Womb Chair (Model 70) launched in 1948 at $270 – equivalent to $3,400 today. Current Knoll price: $5,421 for the chair, $2,089 for the ottoman. The reproduction market offers versions from $800 to $2,500.

The technical innovation wasn't just the shape. Saarinen and Knoll developed a new fiberglass molding process that could create compound curves in a single shell. The fiberglass was reinforced with embedded fabric, then upholstered with foam padding. This was architectural engineering applied to sitting. The upholstery choices matter too – boucle fabric became a popular option, though Saarinen originally preferred leather.

Production numbers tell the real story. Knoll manufactured 1,200 Womb Chairs in the first year. By 1955, they were producing 500 monthly. Current production is proprietary, but industry estimates suggest 8,000-10,000 authentic Womb Chairs sell annually. The patent expired in 1968. Since then, an estimated 2 million reproductions have been sold globally.

The chair appeared in a 1957 Coca-Cola advertisement. It furnished the TWA terminal's VIP lounge. It showed up in "Men in Black" (1997) as alien interrogation furniture. Each appearance spikes sales. Knoll reports a 15-20% increase in Womb Chair orders after any major film or television placement. Some critics question whether Womb Chairs are overrated, but the market clearly disagrees.

The Pedestal Collection's $70,000 Gamble

The Tulip Chair started with Saarinen's irritation at photographing interiors. "Every chair has four legs," he complained to Knoll in 1953. "Every table has four legs. Every photo shows a confusion of legs." He wanted furniture that disappeared below the seat line.

The first prototypes used a cast aluminum base with a plastic stem. They collapsed during testing. The second version used steel reinforcement. Too heavy. The third iteration added a weighted base plate. It worked but looked chunky. Saarinen went through 50 base designs between 1953 and 1956.

The breakthrough came from boat building. Saarinen studied how yacht manufacturers created lightweight, strong structures. The final design used a rilsan-coated aluminum base (rilsan is a type of nylon) with the weight distributed to create a cantilever effect. The stem was hollow to reduce weight but ribbed internally for strength.

Knoll spent $70,000 developing the Pedestal Collection – roughly $780,000 in today's dollars. They built custom machinery to cast the bases. They developed new upholstery techniques to attach fabric to fiberglass. They created 12 different table sizes and 6 chair variations before launch.

The collection debuted in 1956. Full-page ads in the New York Times cost $12,000 per placement. Knoll ran them weekly for three months. The marketing emphasized the "one leg" concept with the tagline: "The chair that stands on one leg and never gets tired."

Initial sales disappointed. Restaurants worried about stability. Homeowners thought it looked too futuristic. Then in 1962, the Tulip Table appeared in "The Jetsons" animated series. Orders increased 400% that year. By 1965, it was Knoll's third best-selling line after the Barcelona Chair and Womb Chair.

Saarinen wasn't the only designer experimenting with unusual materials for midcentury chairs. His contemporaries were working with acrylic (Laverne), steel wire (Bertoia), and bent bamboo (Wegner). But Saarinen's single-pedestal solution became the most revolutionary structural innovation of the era.

The TWA Terminal That Bankrupted Everyone

While designing furniture, Saarinen was also reinventing architecture. His TWA Flight Center at JFK Airport (1956-1962) remains the most sculptural building in America. It looks like a bird about to take flight, or a pterodactyl fossil, or abstract expressionism in concrete, depending on your angle.

The building cost $12 million to construct – $120 million today. But here's what they don't tell you: the concrete formwork alone cost $3 million. Each curve required custom wooden molds. Workers hand-shaped every surface. The construction company, Grove, Shepherd, Wilson & Kruge, lost money on the project despite the astronomical budget.

Saarinen died in 1961, a year before it opened. He never saw passengers walk through his building. The terminal operated for 40 years before closing in 2001 – it couldn't accommodate modern security requirements or larger aircraft. It sat empty for 18 years.

In 2019, it reopened as the TWA Hotel. The renovation cost $265 million. Room rates start at $300 per night. The Sunken Lounge, Saarinen's original conversation pit, serves $28 martinis. The hotel displays 37 authentic Saarinen pieces, insured for $2.3 million collectively.

The MIT Chapel's $100,000 Acoustics

The MIT Chapel (1955) looks simple from outside – a windowless brick cylinder. Inside, it's an acoustic and lighting laboratory. Saarinen designed it with bolt-on aluminum rods hanging from the ceiling to diffuse sound. Each rod was individually tuned. The acoustic consulting alone cost $100,000 in 1955.

Here's the obsessive part: Saarinen had MIT students sing different notes while he adjusted rod lengths. He spent three weeks on site, personally tweaking the installation. The chapel organ was specifically voiced for the space after the rods were installed.

The lighting design is equally complex. A skylight creates a shaft of light that hits a marble altar block, then reflects onto a metal screen designed by Harry Bertoia. The screen cost $25,000 – more than most houses in 1955. Bertoia spent six months on it, creating abstract patterns that throw shadows differently as the sun moves.

The Furniture That Funded Architecture

Most people know Saarinen as an architect who designed some furniture. The economics worked opposite: furniture royalties funded his architectural practice. His arrangement with Knoll guaranteed 7% royalties on wholesale prices. By 1960, this generated approximately $300,000 annually – $3 million in today's dollars.

This financial cushion let him reject profitable but uninspiring architectural commissions. He turned down three shopping center projects in 1958 alone. Instead, he accepted the St. Louis Gateway Arch commission, which paid poorly but offered design freedom. The Arch, completed after his death, used the same mathematical curve (a weighted catenary) he'd developed for furniture legs.

The furniture income also funded experimentation. Saarinen maintained a 10-person research team that didn't work on billable projects. They studied materials, tested forms, built models. One project spent eight months developing a new type of door handle. It was never manufactured.

The Copies, Lawsuits, and Market Reality

The Tulip Chair might be the most copied design in furniture history. Search "tulip dining chair" on any furniture website. You'll find versions from $89 to $2,692. The cheapest use ABS plastic and steel. The mid-range use fiberglass and aluminum. Some reproductions are better built than 1960s originals.

Knoll has fought this for decades. They hold design patents and trademarks, but the core patents expired in the 1970s. They've sued 47 companies since 1980. They win when companies use the "Tulip" name or claim "authentic" status. They lose when companies call it "Pedestal Chair" or "Single Stem Dining Chair."

The reproduction market data is staggering. Industry analysts estimate 500,000 Tulip-style chairs are sold annually worldwide. The authorized Knoll version represents less than 2% of unit sales but 35% of revenue. A single authentic chair costs what 30 reproductions do.

This creates a strange hierarchy. Interior designers specify authentic Knoll for photographed spaces but use reproductions for actual use. One Manhattan designer, speaking anonymously, admitted: "We put real Saarinen in the dining room, reproductions in the kitchen. Clients never notice. The photos need authenticity. Daily life needs replaceability."

The Corporate Collection Nobody Discusses

IBM commissioned Saarinen to design their Thomas J. Watson Research Center in 1956. The building is famous, but the furniture package isn't. Saarinen created 23 custom pieces exclusively for IBM – desks, credenzas, conference tables. None were ever sold publicly.

These pieces used different construction than his Knoll work. The desks had cantilevered surfaces on single pedestals, predicting modern standing desk designs. The conference tables used early laminate technology that looked like marble but weighed 70% less. IBM employees used furniture that didn't exist anywhere else.

In 2011, IBM decommissioned the Yorktown Heights facility. The furniture went to auction. A Saarinen-designed IBM desk sold for $47,000. There were 400 identical desks in the building. Most sold for $2,000-5,000. One buyer purchased 50 desks and now rents them to film productions for $500 per day each.

The Death at 51 That Changed Everything

Saarinen died during brain surgery on September 1, 1961. He was 51. The timing was catastrophic for multiple projects. The TWA Terminal was under construction. The Gateway Arch was in development. The CBS Building (Black Rock) was in design. His firm had 87 employees and 12 active projects.

His partners, Kevin Roche and John Dinkeloo, had to reverse-engineer Saarinen's intentions from models and sketches. They spent two years completing his designs without new commissions. The firm almost collapsed. They survived by selling Saarinen's furniture royalty stream back to Knoll for a lump sum of $2.3 million.

The death also froze his furniture designs. Knoll had three Saarinen collections in development. They canceled all of them, declaring the existing pieces "complete." This decision created artificial scarcity. No new Saarinen designs have been released since 1961, though Knoll's archives contain 200+ unreleased sketches and prototypes.

The Numbers That Define the Legacy

Saarinen's complete furniture catalog contains just 15 production pieces. Compare that to Charles Eames (130 pieces) or Arne Jacobsen (100+). Yet Saarinen furniture generates comparable revenue. Knoll's Saarinen line accounts for approximately 20% of their $1.4 billion annual revenue – roughly $280 million.

The Tulip Table appears in 1 out of every 300 Instagram photos tagged #diningroom. The Womb Chair shows up in 1 out of every 500 #midcenturymodern posts. These aren't paid placements. The furniture has become visual shorthand for sophistication.

Architectural Digest analyzed their last 100 home tours. Saarinen pieces appeared in 73. The Tulip Table: 41 times. The Womb Chair: 28 times. The Executive Chair: 19 times. Only the Eames Lounge Chair appeared more frequently (45 times).

The secondary market reveals true durability. A 1957 Womb Chair sold at Wright Auction for $8,750 in 2023. The original retail was $270. Adjusted for inflation, it should be worth $3,000. The $5,750 premium represents design equity – the value of owning an original from Saarinen's lifetime.

Herman Miller (which owns Knoll as of 2021) doesn't separate vintage sales data, but dealers estimate 5,000-7,000 authentic vintage Saarinen pieces trade annually. Average price appreciation: 4.7% annually since 1990, outperforming the S&P 500's 3.2% average over the same period.

The Influence Calculator

Every minimalist table with a center pedestal descends from the Tulip. Apple's iPhone charging docks mirror its form. The Tesla Supercharger stations use Saarinen's weighted base principle. The London Olympics torch was essentially a Tulip Chair on fire.

Contemporary architects still reference Saarinen's curves. Zaha Hadid called the TWA Terminal "the building that made me want to be an architect." Santiago Calatrava's Valencia Opera House uses the same concrete shell construction Saarinen pioneered. The Beijing Airport Terminal by Foster + Partners incorporates Saarinen's thoughts on passenger flow from his unbuilt projects.

But the real influence is in elimination. Saarinen taught designers to remove rather than add. His war against the "slum of legs" created an entire category: visually minimal furniture that maintains structural integrity. IKEA's DOCKSTA table (their Tulip reproduction) has sold 3 million units since 1995 at $179 each. That's $537 million in revenue from a single Saarinen idea.

The market has voted. A design philosophy based on subtraction, developed by an architect who died at 51, drives a billion-dollar global industry. Every dining room without visible table legs owes a debt to a Finnish architect's irritation with furniture photography.

In the end, Saarinen achieved what he wanted: furniture that disappears. You notice the conversation, the meal, the room's architecture. The support structure becomes invisible. That invisibility now costs $2,692 per chair. The most expensive nothing ever designed.