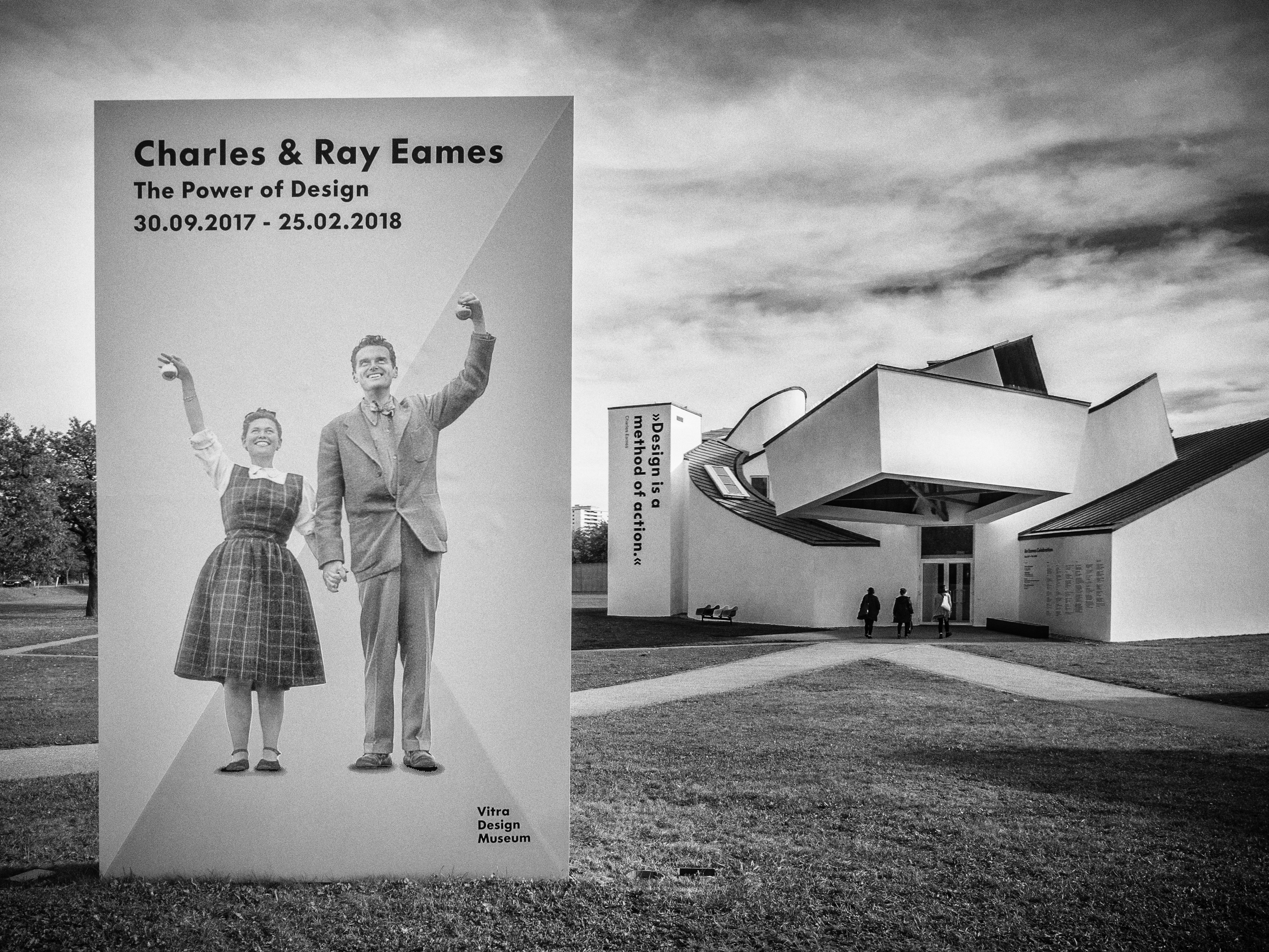

Charles and Ray Eames: The Power Couple of Modern Design

Picture this: It's 1940, and an architect from St. Louis meets a painter from Sacramento at the Cranbrook Academy of Art. Within months, they're married. Within years, they're bending wood in ways that furniture makers said was impossible. Within a decade, they're designing for the U.S. Navy. And eventually, their lounge chair ends up in the Museum of Modern Art's permanent collection.

That's the Eames story in miniature – but the full version involves leg splints, failed experiments with fiberglass in their apartment, and a chair that now costs more than most people's first car.

The Mathematics of Partnership

Charles Eames trained as an architect at Washington University until they expelled him in 1930 for being "too modern." Ray Kaiser studied painting under Hans Hofmann, the abstract expressionist who taught half of New York's art scene. When they met at Cranbrook, Charles was teaching design and Ray was auditing his class.

Here's what the historical record shows: Charles handled the structural engineering and manufacturing relationships. Ray managed color theory, spatial arrangements, and textile selection. Together, they operated like a single creative organism with four hands.

The Eames Office – their Venice, California workshop – employed over 20 designers at its peak. Staff members later described it as part laboratory, part circus. Prototypes hung from the ceiling. Failed experiments became wall decorations. The couple worked seven days a week, often sleeping in the office.

Their design philosophy sounds almost quaint now: "The best for the most for the least." They wanted museum-quality design at department store prices. The market had other ideas.

Plywood Experiments That Changed Everything

Before the Eameses, plywood was what you used for subflooring. Furniture makers considered it cheap construction material, suitable for hidden structural elements but never for visible surfaces. The Eameses saw molecular possibility where others saw lumber yard leftovers.

Their breakthrough came from a simple observation: wood fibers run in one direction, making boards weak across the grain. Layer multiple sheets with alternating grain directions, and you create something stronger than solid wood. Add heat and pressure, and you can bend this composite into compound curves that solid wood would split attempting.

The process sounds straightforward until you try it. The Eameses spent years perfecting the exact temperature (350°F), the precise pressure (50 PSI), and the specific adhesive blend that would hold under stress without yellowing. They built a homemade press in their apartment – essentially a massive waffle iron for wood. Neighbors complained about the smell of cooking glue.

Their first success was the leg splint for the U.S. Navy in 1942. Not furniture, but medical equipment. The Navy ordered 150,000 units. The Eameses used the profits to fund furniture experiments.

The molding technique they developed enabled mass production of complex curves. Before their innovations, curved furniture required steam bending (slow, unpredictable) or carving (expensive, wasteful). Their method could produce identical shells every 12 minutes. The DCM (Dining Chair Metal) from 1946 proved the concept – a chair that could be stamped out like car parts. George Nelson, hired as Herman Miller's design director in 1944, championed this mass-production approach across the company. Original DCMs now trade for $2,500 to $5,000 depending on condition. Herman Miller still produces them for $1,695.

The $8,495 Chair

The Eames Lounge Chair and Ottoman (officially the 670 and 671) took five years to develop. The brief from Herman Miller was simple: create a modern version of the English club chair. The Eameses' interpretation was anything but simple.

Three molded plywood shells, each requiring seven layers of veneer. Die-cast aluminum connectors hidden from view. Leather cushions filled initially with feathers, later with foam. A 15-degree fixed recline angle that orthopedic studies later validated as optimal for lumbar support. The chair rotates 360 degrees; the ottoman doesn't.

When it launched in 1956, demonstrated at the NBC Home Show alongside modernist contemporaries, the set cost $404 (about $4,500 in today's dollars). Current retail from Herman Miller: $5,495 to $8,495, depending on the veneer and leather selection. The secondary market tells an even more interesting story – a 2015 model currently lists for £5,200 on 1stDibs. These chairs appreciate like vintage wines.

The manufacturing process remains largely unchanged since 1956. Each shell still requires hand-assembly. The leather still comes from the same Italian tannery. Herman Miller produces them in Zeeland, Michigan. Vitra manufactures them for the European market in Weil am Rhein, Germany. Both use the original Eames specifications, though collectors can spot the differences: Herman Miller bases have a lower profile, closer to the 1956 original.

There's a famous story about Billy Wilder and his Eames chair – the director was one of the first to own one, a gift from the Eameses themselves. It became his thinking chair, where he wrote some of Hollywood's sharpest dialogue.

Beyond the Famous Chair

The Eameses designed 130 furniture pieces, 42 films, and countless exhibitions. Most people know the lounge chair. Design students know the rest:

The LCW (Lounge Chair Wood) from 1946 demonstrated that plywood could create comfort without cushions. Time magazine called it the "Chair of the Century." Current price: $3,295.

The Hang-It-All from 1953 – a coat rack that looks like molecular structure rendered in painted wood and steel wire. They designed it for children's rooms. Adults bought it for entryways. Still in production: $345.

The House of Cards from 1952 – literally cards with slots that interconnect to build structures. They printed them with patterns from their textile designs and photographs from their travels. Original sets now trade for $500; reproductions cost $35.

Case Study House #8, their own Pacific Palisades home, completed in 1949 using entirely off-the-shelf industrial materials. Steel beams from catalogs. Windows from factory suppliers. The house cost $1 per square foot to build, when custom homes averaged $12. The Eames Foundation still maintains it as a study center.

The Aluminum Group (1958) redefined office seating. Instead of heavy upholstery, they used stretched mesh suspended between aluminum frames. The EA 117, EA 118, and EA 119 became the template for conference room chairs worldwide. Walk into any Fortune 500 boardroom – you're looking at either Aluminum Group originals or their direct descendants. Current price for an EA 119 executive chair: $6,195.

The fiberglass experiments preceded the plywood successes. In 1948, they entered a Museum of Modern Art competition with La Chaise – a flowing fiberglass form inspired by Gaston Lachaise's "Floating Figure" sculpture. Too expensive to produce then, Vitra finally manufactured it in 1991. Current retail: $11,940. It's furniture that nobody sits in, displayed like sculpture in lobbies.

Their wire chairs (DKR, DKW, LKR series from 1951) solved a different problem: how to make a chair that doesn't block sight lines in small spaces. The welded steel rod construction created what they called "a chair made of air." Herman Miller stopped production in the 1960s. Vitra reissued them in 2004. A DKR-2 now costs $1,145 for what amounts to bent metal and a leather pad.

The Eameses weren't alone in experimenting with unusual materials for midcentury chairs – their contemporaries were working with everything from acrylic to aluminum. But the Eameses' systematic approach to material innovation set them apart.

The Films Nobody Watches

The Eameses made films the way they made furniture – with obsessive attention to detail and complete disregard for conventional structure. "Powers of Ten" (1977) zooms from a picnic blanket to the edge of the observable universe and back to subatomic particles in nine minutes. Science teachers still screen it. Art students study its structure.

"Glimpses of the U.S.A." (1959) projected on seven screens simultaneously at the American National Exhibition in Moscow, showed 2,200 images of American life in 12 minutes. Khrushchev watched it. So did Nixon. Both claimed it supported their worldview.

IBM commissioned 12 films between 1957 and 1979. Titles like "The Information Machine" and "A Computer Perspective" attempted to make mainframe computers seem friendly. Watching them now feels like archaeology – they document the exact moment when computers shifted from military hardware to business tools.

The Archive as Artwork

Ray Eames photographed everything. Not casually – systematically. The Eames Office archive contains approximately 750,000 photographs and slides. She documented prototypes, factory visits, design iterations, failed experiments, successful launches, office parties, and casual Tuesdays.

This visual documentation practice changed how design studios operate. Before the Eameses, designers kept sketches. After them, everyone kept photographic process journals. Ray's compositional eye – trained in abstract painting – turned mundane documentation into artistic record. Her photograph of stacked DSR chairs from 1951 became more famous than most designers' finished products.

The Library of Congress acquired the complete archive in 2014. Researchers can request boxes of slides showing 47 different attempts at a single chair joint, each photographed from six angles. It's the design process turned into data.

The Replica Economy

Search "Eames-style chair" on any furniture website. You'll find hundreds of replicas ranging from $400 to $2,000. Some use "7-ply construction" as a selling point. Others advertise "improved 8-layer plywood" – a red flag for anyone who understands the original engineering.

The patent expired decades ago. Anyone can legally manufacture an Eames-design chair. Herman Miller and Vitra hold trademark rights to the Eames name, not the design itself. This creates a strange market: authorized "authentic" versions that cost $8,000, and unauthorized "replicas" that cost $800, often made to the same specifications.

The replica market reveals something about design value. When people pay $8,000 for a Herman Miller version, they're buying more than bentwood and leather. They're buying providence, heritage, and the specific factories that the Eameses personally worked with. It's the difference between a Stradivarius and a violin that sounds like a Stradivarius.

By 1962, the replica situation had gotten so widespread that Herman Miller took out advertisements warning about counterfeits. The ads didn't threaten legal action – they appealed to design integrity. "There is a difference," the headline read, showing side-by-side comparisons of authentic and replica joints. The market ignored the plea.

What the Museums Keep

The Museum of Modern Art owns 35 Eames pieces. The Victoria and Albert Museum has 250. The Library of Congress holds their complete film archive. These aren't nostalgic collections – they're working references for contemporary designers.

Apple's Jonathan Ive studied Eames joinery for the iPhone's construction. Herman Miller's current designers regularly reference the Eames archive for proportion guidelines. The couple's color combinations appear in everything from Google's Material Design to IKEA's annual catalog.

The mathematical ratios they used – particularly the golden ratio in their shell chairs – show up in contemporary automotive design. Tesla's Model S seats use similar compound curves. BMW's i8 interior follows Eames-established ergonomic angles.

The Numbers Game

Ray Eames died on August 21, 1988, exactly 10 years to the day after Charles died on August 21, 1978. They left no children together, but the Eames Office continues under the direction of Lucia Eames, Charles's daughter from his first marriage, and her children.

Herman Miller's annual report doesn't break out Eames sales specifically, but industry analysts estimate the lounge chair alone generates $50-75 million annually. For a design that's 69 years old, those numbers suggest something beyond furniture.

The complete Eames catalog generates an estimated $200-300 million annually across all authorized manufacturers. The Plastic Shell Chairs (DSW, DSR, DAW, DAR variants) account for roughly 40% of sales volume. The Aluminum Group represents another 25%. The famous Lounge Chair, despite its price, drives 20% of revenue due to margins.

The Eames Estate (managed by the family) collects licensing fees from Herman Miller, Vitra, and various smaller manufacturers producing authorized accessories. The estate doesn't disclose numbers, but trademark filings suggest seven-figure annual revenues from licensing alone.

Meanwhile, the replica market – completely legal, completely unauthorized – probably doubles those numbers. A furniture design that predates the Kennedy administration drives a nine-figure global market.

The production numbers tell their own story. Herman Miller has manufactured over 6 million shell chairs since 1950. Vitra has produced approximately 150,000 Lounge Chairs since acquiring European rights in 1957. The Aluminum Group has furnished an estimated 60% of Fortune 500 conference rooms at some point since 1958.

The Permanent Influence

Walk through any contemporary design museum. The curved plywood, the exposed mechanical connections, the honest use of materials – these Eames principles appear everywhere. They didn't invent modernism, but they made it comfortable enough to sit in.

Their true innovation wasn't bending wood or molding fiberglass. It was proving that experimental design could be mass-produced. That avant-garde ideas could become living room furniture. That a chair could be both an art object and a place to read the newspaper.

The price trajectory tells its own story. What started as democratic design became luxury goods. The couple who wanted "the best for the most for the least" created objects that now cost more than most people's monthly rent. The market transformed their populist vision into elite consumption.

Yet reproductions keep their original dream partially alive. For $600, anyone can own something that looks exactly like an Eames lounge chair. It won't have the providence, the specific grain patterns that Ray selected, or the Herman Miller stamp. But it will have the same angles, the same proportions, the same fundamental comfort that took 15 years to perfect.

The Eames design DNA shows up in unexpected places. Apple's iPhone packaging follows Eames principles: reveal the object, celebrate the material, make unpacking an experience. Tesla's minimalist interiors echo the Eames philosophy of exposing functional elements as decoration. IKEA's entire business model – democratic design at scale – descends directly from the Eames manifesto, even if their price points finally achieved what the Eameses couldn't.

That's the Eames paradox: designs so successful they escaped their creators' intentions, yet so distinctive they remain instantly recognizable 70 years later. Every modernist chair since 1956 exists in conversation with their work – either embracing their principles or deliberately rejecting them.

In design terms, that's immortality.