The Baseball Mitt Chair: How Billy Wilder's Nap Problem Became Design History

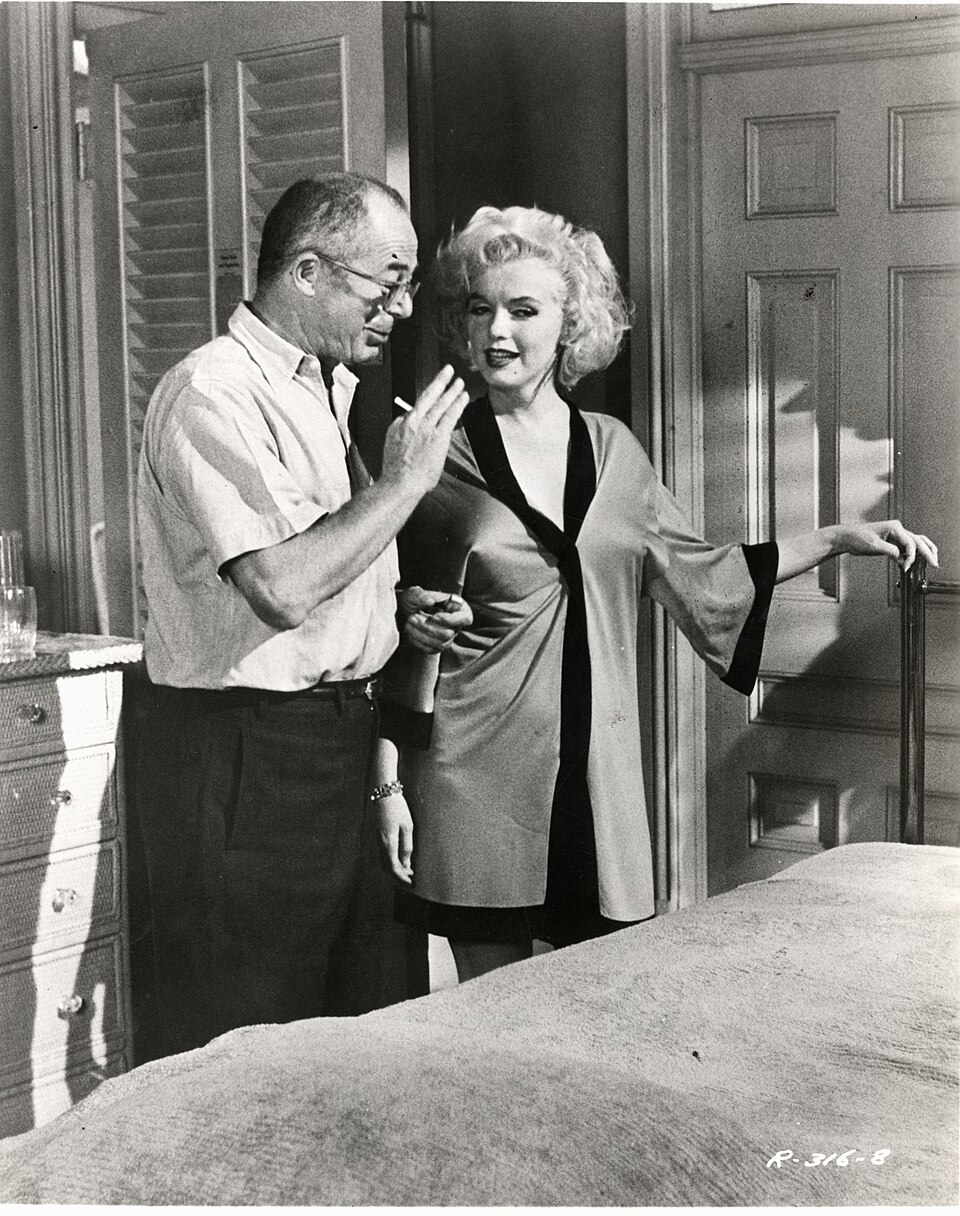

Billy Wilder directing Marilyn Monroe during Some Like It Hot (1959). Photo: Touring Club Italiano, CC BY-SA 4.0"

Charles and Ray Eames had a reputation problem in 1956. Everyone knew they could make furniture that was affordable, practical, and mass-produced. Their molded plywood dining chairs sold 18,000 units in a single year. Their fiberglass shells sat in thousands of schools and restaurants across America. They'd made splints for wounded soldiers during the war, chairs for offices, tables for homes. Democratic design, in the most literal sense - furniture that anyone could afford.

But they'd never made anything expensive.

The entire Eames philosophy revolved around getting "the best to the most for the least." Every previous design had been explicitly created for everyone. So when they announced they were working on a luxury lounge chair, it raised questions. Why would two designers who'd spent a decade perfecting mass-market furniture suddenly pivot to something that would cost more than most Americans made in a week?

The answer, according to Charles, was surprisingly simple. They wanted to create "the warm, receptive look of a well-used first baseman's mitt."

Now, that's the thing about that description. It's not about newness or pristine leather or showroom gleam. A well-used baseball glove has been broken in. It's shaped itself to a hand through thousands of catches. It smells like leather and grass and summer. It's the opposite of stiff, the opposite of formal, the opposite of trying to impress anyone. A first baseman's mitt that's seen some action doesn't care about your credentials. It just wants to catch the ball.

And that's exactly what they built.

The English Club Chair Problem

The official story is straightforward: Charles wanted to create a modern version of the traditional English club chair. Those nineteenth-century leather armchairs that lived in wood-paneled libraries and gentleman's clubs. The kind of furniture that represented a certain kind of established comfort, but in a way that felt dated by the 1950s.

The challenge was translating that feeling - deep leather, substantial presence, the sense of sinking into something that would hold you - into something that looked like it belonged in a post-war American living room. Not an antique. Not trying to recreate the past. Just capturing what made those club chairs work and rebuilding it using the materials and techniques that Charles and Ray had spent a decade perfecting.

Now, there's also folklore. Some sources mention their friend Billy Wilder - the director behind Sunset Boulevard and Some Like It Hot - and his habit of improvising naps on film sets between takes. The story goes that watching him struggle with makeshift seating inspired the lounge chair. But the timeline is fuzzy, and the Eames Office itself doesn't cite Wilder as the direct inspiration for the 1956 lounge chair.

What's definitely true: Charles and Ray were close with Wilder. Close enough that they stood up in his wedding. Close enough that he asked them to design him a house (plans fell through when his wife objected to all that glass). Close enough that Charles produced a montage sequence for Wilder's 1957 film The Spirit of St. Louis.

And in 1968, twelve years after the lounge chair debuted, they did make Wilder a chair - the ES106 Chaise. That one has clear documentation: Wilder mentioned needing a narrow office daybed after using a plank on sawhorses during filming, and Charles and Ray delivered exactly that. The lounge chair's origin story? Less clear, more debated, probably just what Charles said it was: a modern take on the English club chair.

The $310 Problem

When the Eames Lounge Chair (model 670) and Ottoman (671) hit the market in 1956, they sold for $310. That's roughly $3,100 in 2026 money. For context, that's about what you'd pay for a decent used car in 1956.

This presented Herman Miller with a marketing challenge. How do you sell an expensive chair from designers famous for affordable furniture? How do you convince someone to spend that kind of money on a seat when they could furnish their entire living room with other Eames pieces for the same price?

The advertising got creative. One ad positioned it as "the only modern chair designed to relax you in the tradition of the good old club chair." Translation: this is fancy, but in a new way. Another angle leaned into bachelor pad luxury - Playboy magazine featured it prominently in the 1960s. The chair became furniture for a very particular aspirational lifestyle.

Arlene Francis, hosting NBC's Home show for the national debut in 1956, called it "quite a departure" from the Eameses' earlier work. She was being diplomatic. It was a complete reversal.

What Makes It Feel Like a Baseball Mitt

Here's where the engineering gets interesting. The chair doesn't just look comfortable - it's designed around specific biomechanical principles that the Eameses had spent years refining.

Three separate shells make up the frame: base, backrest, headrest. Each one is molded from five layers of plywood (later changed to seven layers in the 1970s for stability). Brazilian rosewood veneer covered those original shells - gorgeous, expensive, and eventually banned for environmental reasons. Current versions use cherry, walnut, or sustainably grown palisander rosewood.

The recline angle is fixed at 15 degrees. Not 10. Not 20. Fifteen. That's the sweet spot where your spine relaxes without your body sliding forward. The seat cushions and ottoman cushions are identical in size and shape - they're interchangeable. This wasn't an aesthetic choice. It was practical. Manufacturing efficiency, yes, but also: if one wears out, you've got options.

Those cushions were originally filled with down feathers. Luxurious, traditional, and completely impractical for furniture that people actually use. By 1971, Herman Miller switched to foam. Less romantic, far more durable, and honestly more comfortable for long sitting sessions.

The base has five legs instead of four. That's about stability - a five-point base eliminates wobble on any floor surface. The chair swivels 360 degrees. The ottoman doesn't. Early prototypes had a rotating ottoman, but Charles and Ray decided it was unnecessary. The ottoman's job is to stay put while you rest your feet on it, not spin around.

Shock mounts - those small rubber pieces between the aluminum frame and wooden shells - came from their earlier work on the DCM dining chair. They add resilience, a slight give when you sit down. Small detail, massive difference in comfort.

The Manufacturing Problem Nobody Talks About

Making these chairs is still largely done by hand. That's not a romantic choice or a marketing story. It's a technical necessity.

The plywood shells are molded using heat and pressure - the same technique the Eameses developed making leg splints for the Navy during World War II. Individual veneer sheets are stacked with alternating glue-coated and dry layers, then heated to exactly the right temperature while pressure bends them into organic curves.

Getting that process consistent across thousands of chairs? That's the engineering challenge. Wood is a natural material. Grain patterns vary. Moisture content varies. Each shell needs individual attention to ensure it matches the specifications. You can't fully automate that without accepting inconsistent quality.

Herman Miller's factory workers polish each shell by hand. They assemble the aluminum frames. They attach the leather cushions, checking that the tufting sits evenly, that the zippers (brown or black on early models, later all black) are positioned correctly. The little details - screw placement, spacer material, the "domes of silence" rubber feet - all changed slightly over the decades as manufacturing improved, but the core process remains recognizably the same as it was in 1956.

This is why authentic Eames lounge chairs cost $5,000 to $10,000 in 2026. Not because of the name, although that doesn't hurt. Because making them well requires actual craftsmanship.

What Billy Wilder Actually Got

Wilder did eventually get his chair - just not the famous one. In 1968, twelve years after the lounge chair debuted, Charles and Ray designed the ES106 Chaise specifically for him. Narrow (17.5 inches wide), long (six feet), curved, and upholstered in leather with six separate cushions tied to an aluminum frame.

The design had a built-in alarm clock: lie down, fold your arms across your chest, and within minutes your arms would slip off and wake you up. Perfect for someone who wanted a power nap without sleeping through the afternoon.

That's the chair that directly came from Wilder's request. The lounge chair? That was the Eameses doing what they did best - seeing a broader need (comfortable, modern luxury seating) and solving it in a way nobody had quite managed before.

Why This Chair Ended Up in a Museum

The Museum of Modern Art acquired an original 1956 rosewood Eames Lounge Chair and Ottoman in 1960. Herman Miller donated it. Four years after its debut, MoMA decided this qualified as significant 20th-century design worthy of permanent collection status.

That's unusually fast recognition for furniture. Most design pieces don't get museum placement until decades after creation, when historical significance becomes clear. But MoMA saw immediately what the chair represented: a successful marriage of traditional luxury (the English club chair, expensive materials, handcrafted quality) with modern manufacturing techniques (molded plywood, mass production capability, contemporary aesthetics).

It also sits in the permanent collection at the Art Institute of Chicago. There's one at the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan. These aren't just decorative pieces. They're documents of a specific moment when American design figured out how to be both modern and luxurious without choosing between the two.

The Replica Market They Created

The chair became one of the most counterfeited furniture designs in modern history. By 1962 - six years after launch - the problem was bad enough that the Eameses took out full-page newspaper advertisements warning consumers about fakes.

That's a strange position for designers who spent their careers trying to make good design accessible to everyone. But there's accessible, and then there's lying about what you're selling. The counterfeits weren't cheaper versions of the same quality. They were inferior products trading on the Eames name and the chair's iconic silhouette.

Chinese manufacturers, European companies, and American competitors like Plycraft all produced direct copies or heavy imitations. Some were honest replicas - clearly marketed as inspired-by versions at lower price points. Others claimed to be authentic.

Herman Miller and Vitra (the European manufacturer authorized by the Eameses) remain the only two companies legally producing chairs with the Eames name. Everything else is either vintage or a reproduction.

The interesting part? The chair's design is so recognizable that even obvious replicas benefit from its reputation. That silhouette - the three curved shells, the proportions, the five-star base - became visual shorthand for mid-century modern sophistication. Whether it's authentic or not almost doesn't matter to casual viewers. It signals taste, design awareness, a particular aesthetic sensibility.

The Frasier Effect and What Came After

Pop culture adopted the chair enthusiastically. The TV show Frasier called it "the best-engineered chair in the world" and featured it prominently. James Bond films used it as set decoration. There's a famous photograph from a joint interview where Steve Jobs sits in the Eames lounge chair while Bill Gates perches on the ottoman - two tech titans sharing one furniture set.

That image says something about what the design came to represent. Not just comfort or good taste, but a specific kind of thoughtful, design-conscious success. The chair became furniture for people who care about how things are made, who appreciate the difference between something done well and something done adequately.

Reddit has dedicated communities for "Eames Enthusiasts." Instagram is full of carefully composed photos featuring the chair in meticulously designed spaces. Resale sites like 1stDibs list vintage 1956 models for $17,500. The chair has sustained a cult following for nearly 70 years, which is unusual for any consumer product, let alone furniture.

Materials That Changed With the Times

The original 1956 chairs used Brazilian rosewood for the shells. Beautiful, distinctive grain patterns, and by the early 1990s, banned for export due to environmental concerns. Herman Miller adapted. They introduced seven-layer plywood shells for better stability and switched to alternative woods: cherry, walnut, American white ash, Santos palisander.

In 2006, for the 50th anniversary, they released a special edition using sustainably grown palisander rosewood - visually similar to the original Brazilian version, legally and ethically sourced. The chair evolved without losing its essential character.

More recently, both Herman Miller and Vitra introduced a "tall" version in 2008. The original 1956 dimensions were based on 1950s average body sizes. People got taller. The tall version adds 1.75 inches to the overall height and half an inch to seat height. Small adjustments, but they make the chair work for users who would've felt cramped in the original.

The latest innovation? Plant-based upholstery made primarily from bamboo, introduced in 2024. It reduces the chair's carbon footprint by up to 35 percent compared to traditional leather. The price ($6,395) stays firmly in luxury territory, but at least it's luxury that considers its environmental impact.

What the Chair Actually Represents

Here's what's interesting about the baseball mitt comparison. A first baseman's mitt doesn't try to look expensive. It tries to work perfectly. The leather is thick because it needs to catch 90 mph fastballs repeatedly without falling apart. The pocket is deep because that's what physics and ergonomics require. Form follows function, and the beauty emerges from that relationship.

The Eames Lounge Chair does the same thing. The 15-degree recline exists because that's the angle where most people's spines relax. The five-star base exists because that's what stability requires. The separate shells exist because manufacturing identical cushions is more efficient than custom-fitting each one. The shock mounts exist because a tiny bit of give makes sitting down feel better.

Every design choice serves a purpose beyond aesthetics. The chair looks the way it does because that's what comfort looks like when you're paying attention to how humans actually sit.

Charles and Ray Eames built their reputation making furniture for everyone. The lounge chair was their one major exception - a piece that cost real money, used premium materials, took significant time to manufacture. But even that expensive chair adhered to their core principle: solve the problem well, and the design follows naturally.

That's why it ended up in museums. That's why it's still in production nearly 70 years later. That's why people spend five figures on vintage examples. Not because it's famous, although it is. Because it works exactly as well as Charles and Ray said it would, back when they were trying to bottle the feeling of a well-worn baseball glove into a piece of furniture.

They succeeded. And somewhere in there, unusual materials became luxury, and a Hollywood director's nap problem became a small part of design history.